Smokestack (buck)

- Velvet 3×3 antler frame; slightly forward beams

- Narrow face; dark muzzle patch

- Expect velvet shed late Aug/early Sept; pre‑rut activity by Oct

AIS

AIS

Documenting an urban wildlife corridor along the Fredericksburg swamp edge using camera traps and field logs.

OPEN MISSION PAGECamera traps placed where riparian forest meets old industrial berms reveal a consistent deer travel route. Our initial dataset captured a velvet‑antlered buck, an adult doe, and her spotted fawn. We summarise their identifiers, expected seasonal changes, and habitat patterns, then outline next steps for long‑term monitoring.

We live alongside the Rappahannock. The riparian edge, old berms and service lanes create a pinch‑point corridor that concentrates movement for deer and other species.

One can consider the swamp a wildlife corridor node: it connects with the linear corridor of the Rappahannock River, allowing animals (and plant propagules) to move along the riparian zone through downtown.

For example, an otter or muskrat could travel via the river and use this swamp for denning and feeding. Birds and bats follow the green ribbon of trees along the river. Importantly, just upstream and downstream are larger green spaces (Old Mill Park upstream, city parkland downstream), so this swamp serves as a stepping stone between habitats – a refugium for species moving along the Rappahannock River Wildlife Corridor.

However, being in an urban area, the ecosystem faces stresses: invasive species (as noted, plants like stiltgrass and animals like the prolific Norway rat); polluted runoff from streets (oil, trash, and nutrients wash into the swamp via storm drains and the river); and disturbance from humans (trespassing, dumping, etc.).

Despite these, the swamp appears to maintain a high ecological value by virtue of being largely undeveloped and difficult to traverse (which ironically protects it by limiting human intrusion). Continued naturalization – possibly aided by planned conservation projects – could further improve its habitat quality.

Geology and Soils: Fredericksburg’s fall line sits atop hard ancient bedrock that surfaces along the river. Exposures of biotite gneiss and two-mica schist of the Po River Metamorphic Suite underlie this area. These Piedmont rocks formed in the Late Proterozoic–Paleozoic and create the river’s rapids and rocky shoals.

Immediately east, the Coastal Plain’s softer sandy sediments begin – but in the swamp vicinity, any coastal deposits are thin, as the site lies at the very transition. Overlying the bedrock and filling the floodplain is recent alluvium: a mix of silty sand, gravel, and organic muck deposited by the Rappahannock. The swamp’s soils are waterlogged and high in organic content, characteristic of a wetland in a riverine floodplain. They likely correspond to a poorly drained fluviatile soil series (e.g. Chagrin or Manco series on floodplains, which have loamy alluvium) – with dark, anaerobic upper horizons from accumulating plant matter.

Any prior construction (canal embankments, building foundations) has also influenced local soils, introducing areas of fill and compaction.

Surface Hydrology: The swamp is part of the Rappahannock River’s floodplain and hydrologically linked to the river’s flow regime. With Embrey Dam gone, the river here experiences natural fluctuations: rapid rises during storms and seasonal high flows, and lower baseflows revealing rocky channels. The site sits just above tidal influence (the fall line is the limit of tides), so the swamp’s water levels are driven by rainfall and river flooding rather than daily tides.

During flood events, the swamp and adjacent lowlands act as a sponge – river water spreads out into these flats, slowing and depositing sediment. Recent flood crest records at Fredericksburg (e.g. ~22–25 feet in 2014 and 2018) indicate extensive inundation of the floodplain. Evidence of flood scouring and deposition is visible on the ground: layers of silt, driftwood racks, and flattened vegetation in images of the swamp’s interior (e.g. matting of reeds and debris in field photos).

Outside of flood pulses, parts of the swamp hold standing water perennially. This results from a combination of poor drainage (impervious clay lenses and flat topography) and possibly remnant features of the canal. The old power canal/sluice that once ran through or alongside this swamp may still channel water or impede its outflow.

After the Embrey Dam removal, the main canal was de-watered as a managed channel, but rainfall and groundwater now collect in its trench. The LiDAR topography shows a linear depression and berm – consistent with the canal’s path – running through the site. This likely traps water, effectively creating a long pond or series of marshy pools parallel to the river.

Additionally, any low former impoundment areas that were once kept artificially high by the dam have now partially drained, but not entirely: saturated sediments left behind have settled unevenly, forming pockets that retain water. The swamp’s hydrology is thus a mosaic of slow-flowing backwaters, cutoff channels, and rain-fed ponds.

Groundwater and Wetland Dynamics: The proximity to the river means the local water table is high. Groundwater in the alluvial aquifer rises and falls with river stage. In drier times, seepage from the river and upland slopes maintains soil moisture in the swamp; in wetter times, the water table intersects the surface, contributing to standing water. The swamp can be classified as a palustrine forested wetland transitioning to scrub-shrub and emergent marsh in parts.

Its wetland dynamics include seasonal drying of some patches (especially in late summer or drought) and re-wetting with precipitation or river flooding. Such fluctuations influence the plant community (favoring species that tolerate both inundation and exposure). The lack of strong tidal flushing or a defined inlet/outlet means water in the swamp is relatively stagnant; dissolved oxygen drops in pooled areas, especially in warm months, creating anoxic soil conditions. This slows decomposition and fosters peat buildup.

The wetland’s extent may be increasing post-dam: as the river channel has narrowed to its natural banks, some of the former impounded margins are converting to marshy ground with pioneer wetland plants colonizing the newly exposed mudflats. Over time, the swamp could evolve further if beaver activity (observed elsewhere on the Rappahannock) raises water levels, or if heavy floods scour channels through it.

Already, standing dead trees in the photographs suggest a significant hydrologic change: likely trees that grew when the ground was drier have recently died due to increased water saturation (a pattern often seen after beaver pond creation or drainage changes).

In sum, the swamp’s hydrology is a dynamic interplay of river flood pulses, remnant canal structure, and groundwater, leading to a diverse wetland habitat that is still adjusting to the post-dam river regime.

Despite its urban context, the swamp and surrounding riparian corridor host a surprisingly rich ecosystem. Freed from industrial use for 60+ years, the area has rewilded. Vegetation ranges from mature wetland trees around the periphery to dense herbaceous cover in the constantly wet interior.

Based on field observations and regional species, the swamp’s flora likely includes:

Overall, the swamp’s ecosystem function is that of a typical riparian wetland – it provides floodwater storage, slowing and absorbing surges (protecting downstream areas by damping peak flows). It also filters pollutants and sediment from urban runoff and river water. Nutrient-rich sediment is deposited here, and wetland plants uptake nitrogen and phosphorus, improving water quality. The thick vegetation and standing water create a microclimate of cooler, humid conditions that can serve as a refuge for wildlife during heat waves. The standing dead trees (“snags”) and logs enhance detrital food webs, supporting fungi, insects, and amphibians that break down organic matter. In sum, this swamp performs valuable services: flood mitigation, water purification, carbon sequestration in its accumulating peat, and biodiversity support – an ecological green spot within the city.

Wildlife: The swamp and adjacent river support a diverse fauna, some species surprisingly large for an urban setting. On the macro scale, the removal of Embrey Dam in 2004 reopened migratory fish passage; now anadromous fish like American shad, river herring, and striped bass seasonally move upriver past this area. This has likely enriched the food supply for predators.

Notably, bald eagles are frequently observed – local residents report hearing and seeing eagles near the Embrey Power Station site. These eagles perch in tall riverside trees or on the derelict structure and hunt fish in the river, indicating a functional aquatic food chain. Ospreys also fish here in warmer months. Wading birds such as great blue herons and egrets stalk the shallow water for fish, frogs, and crayfish. The swamp’s quiet pools may harbor wood ducks or mallards nesting in cavity trees and feeding on duckweed.

On the ground and in the water, one would expect amphibians (leopard frogs, green frogs, spring peepers in wetter parts, and salamanders in the leaf litter during moist conditions). Reptiles include water snakes (Northern water snake) and possibly snapping or Eastern painted turtles in the deeper pools.

The presence of numerous downed logs and a mix of open water and dense brush is ideal for beavers – indeed, beavers have been documented along the Rappahannock in Fredericksburg, and they may have a lodge or dam nearby. If beavers actively manage the swamp, they’d contribute to keeping it flooded by damming any drainage ditches, thus creating more standing water and further deadening trees (consistent with what we see). Their gnaw marks would be evident on felled timber. White-tailed deer likely pass through for water and shelter, and raccoons, opossums, and red foxes forage along the water’s edge (especially at night).

Smaller creatures abound: dragonflies and damselflies patrol the air over the water eating mosquitoes; lush vegetation supports butterflies and moths. In summer, expect a chorus of insects (crickets, katydids) and tree frogs. The detritus-rich swamp floor is prime for invertebrates – snails, mussels (if any survived historical pollution, perhaps Eastern floater or other hardy bivalves in slow water), earthworms, and myriad aquatic insects that feed fish and amphibians. The ecosystem’s trophic structure is thus quite complex for a city locale, from algae and aquatic plants up to apex avian predators.

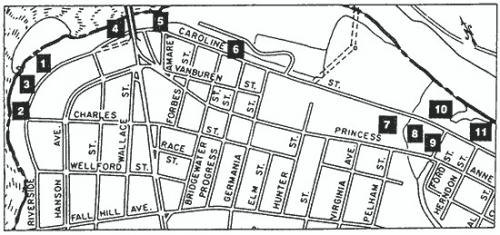

The swamp in question lies on the south bank of the Rappahannock River in downtown Fredericksburg, adjacent to the abandoned Embrey Power Station (the former hydro-electric plant). This locale sits at the Fall Line, where the river’s rocky rapids mark the boundary between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain.

Historically, this area has been a critical nexus of human activity – from Indigenous use of the rich riverine resources, through colonial-era industry, to 19th–20th century waterpower and hydroelectric development.

Understanding this site’s past is crucial to interpreting its present ecological state and guiding future stewardship.

Indigenous Presence: For centuries before European colonization, the Rappahannock fall line was a seasonal gathering and fishing ground for Native peoples. Algonquian-speaking groups of the Powhatan chiefdom (notably the Rappahannock tribe, whose name means “people who live where the water rises and falls”) were encountered by Captain John Smith in 1608. Upland of the falls, Siouan-speaking Mannahoac communities also frequented the area according to early English reports.

Archaeological records indicate a hunting camp near a large island at the falls, on the Fredericksburg side of the river. Such sites yielded stone tools and other evidence that Indigenous people took advantage of abundant migratory fish and game at the falls for millennia. The falls likely featured fish weirs and favored camping spots, though no major permanent village is documented directly at today’s downtown.

As English settlers arrived, conflict and displacement followed – e.g. in the late 1600s the colonial militia established a fort near the falls to secure the area. By the early 18th century, Native presence had been greatly diminished or driven upriver, paving the way for European town development.

Colonial and Early Industrial Use: The Virginia House of Burgesses in 1728 chartered Fredericksburg at the fall line to serve as a trading hub linking tidewater markets with upstream territories. The swift drop of ~22 feet in river elevation over a mile made the site ideal for water-power. As early as the 1720s, colonists built dams and watermills on both banks to grind grain and saw wood.

Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, numerous grist mills, iron works (such as Spotswood’s Tubal Furnace upriver), and other enterprises clustered along the river. By 1816-1849, investors constructed the Rappahannock Navigation Canal system to bypass rapids and improve commerce. This ambitious system included multiple small dams and side canals; one canal segment skirted the Fredericksburg falls, enabling bateaux to carry inland wheat and iron to the port. However, the navigation company never turned great profits.

After the Civil War, many old mills lay in ruins – the Battle of Fredericksburg (1862) saw occupying troops damage or destroy watermills, and postwar economic malaise left industrial sites underutilized.

Water Power and Hydroelectric Development: Desperate to revitalize industry, Fredericksburg embraced hydroelectric power in the late 19th century. In 1855, the Fredericksburg Water Power Company purchased the defunct canal works and converted them for power generation.

A wooden crib dam was built just above Hunter’s Island (a large island at the falls) to divert river flow into a new power canal. By the 1880s, local entrepreneurs leveraged this canal: in 1887 the Rappahannock Electric Light & Power Company was founded and installed dynamos in an old mill (Knox’s sumac mill) at what is now Old Mill Park. Using 50 horsepower of water diverted from the canal, this small plant lit Fredericksburg’s streets with electric light for the first time on November 3, 1887. It was among Virginia’s earliest hydroelectric endeavors.

The city soon decided to generate power itself – in 1901 the municipally-run City Electric Light Works opened on the upper canal (between the Washington Woolen and Germania mills). This two-story plant, completed in 1901, allowed the city to economically power streetlights and homes without outsourcing to the private company. (It operated until 1919 before shutting down.)

The most significant development came in 1909–1910 when industrialist Frank J. Gould (having acquired the Water Power Co.) financed a new dam and hydroelectric station. The Embrey Dam, a 22-foot-high concrete gravity dam at the fall line, was finished in 1909. It created a mile-long impoundment and fed an upgraded power canal.

In 1910–1911, the adjacent Embrey Power Station (sometimes called Spotsylvania Power Company Power House No.1) was completed. Designed by engineer Cecil L. Reid, this plant was built of reinforced concrete and steel – a cutting-edge design echoing contemporary powerhouses in Richmond.

Six remotely-operated sluice gates at Embrey Dam controlled flow into the canal feeding the plant. Water from the canal dropped via underground penstocks into turbine pits, then was discharged back to the river. The power station’s generators (dynamos) produced up to 3,000 kW of alternating current, electrifying Fredericksburg and surrounding areas.

By 1923 it served over 1,000 customers, and by 1926 over 2,000 customers. That year, the operation was sold to Virginia Electric & Power Co (VEPCO) and tied into the regional grid. The plant gave Fredericksburg remarkably low electric rates and spurred industrial growth.

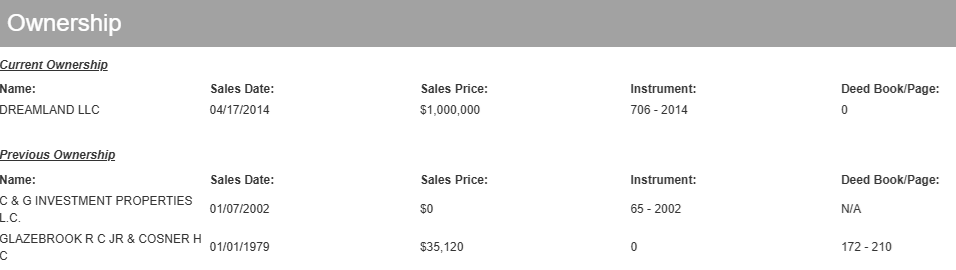

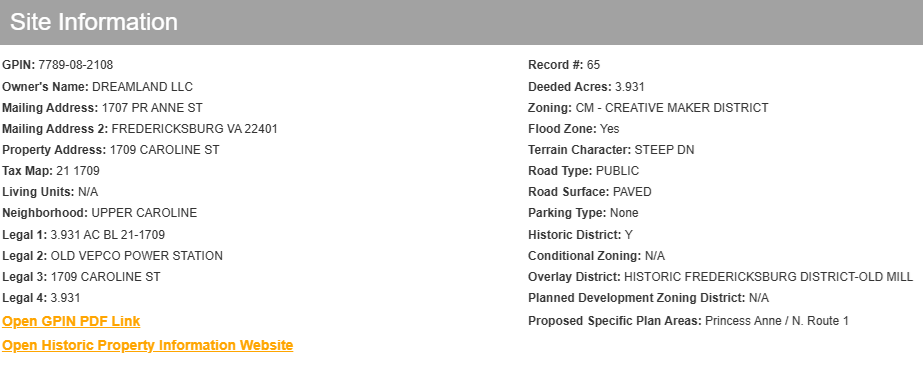

The land encompassing the swamp and the abandoned hydroelectric plant is primarily privately owned, though it sits amid public interests.

According to city records, the Embrey Power Station property (approx. 4 acres at 1704/1709 Caroline Street) was purchased by a private entity, Dreamland LLC, around 2013–2014 for redevelopment. Local news reported the sale price was about $1 million.

Dreamland LLC is controlled by a Fredericksburg businessman who initially proposed a mix of adaptive reuse (a restaurant in the old power house) and new construction (condos and parking) to capitalize on the riverfront location.

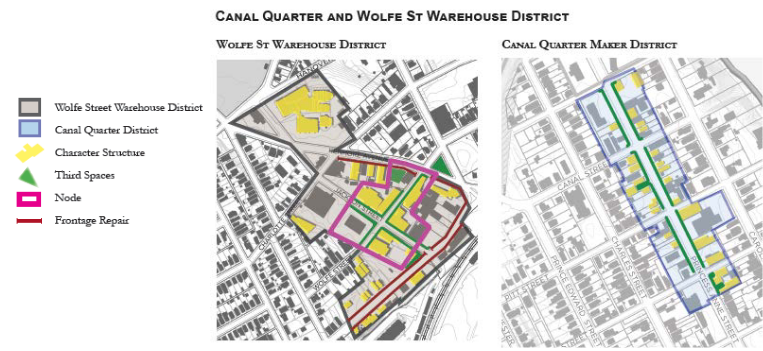

The site lies within Fredericksburg’s Area 6 “Creative Maker District,” a special zoning district created to encourage revival of the Princess Anne Street/riverfront corridor with artisan businesses, mixed-use development, and historic preservation.

In fact, a rezoning to a Planned Development–Mixed Use (PD-MU) was pursued to enable a project combining the power station, the nearby Silk Mill, and other parcels into a cohesive development. That plan – sometimes dubbed the “Mill District” – envisions new residential units and commercial space while reusing the historic Embrey power plant structure (which dates to 1910–11 and retains its concrete shell and some machinery).

Current zoning for the swamp/power plant parcel reflects these intentions. It is no longer strictly industrial; under the “Creative Maker District,” guidelines, permitted uses include light manufacturing, studios, breweries, etc., alongside residential and retail (with special exceptions).

Any new development must also respect the site’s historic character – the power station is regarded as a historic asset (it was designed by notable engineer Cecil Reid in 1909, and while not individually on the National Register, it’s part of Fredericksburg’s industrial heritage).

The city’s 2015 Small Area Plan for this district specifically mentions “adaptive reuse of the Embrey Power Station and older historic mills” as a goal.

Ownership and Easements: Aside from the private core, portions of the adjacent land may involve public easements. The Rappahannock Heritage Trail – a paved greenway – runs very close to this site, passing just west of the power station along Caroline Street and linking to the canal path.

There are likely utility or access easements for the trail and for maintaining the canal’s remnants (the city still owns the old canal ditch in many places). It’s possible that a conservation easement or covenants exist along the riverbank itself. Fredericksburg’s 2006 conservation initiative placed over 4,000 acres of city-owned riparian land under permanent easement, but that mainly covered upstream forests acquired for water supply. The downtown swamp parcel was not city-owned and thus not included.

However, it is subject to multiple environmental regulatory overlays:

Current Status: As of 2025, no major construction has occurred – the power plant remains abandoned but secured (the owner did some graffiti cleanup and stabilization).

A nonprofit group, RIVERE, has emerged with a vision to transform the site into an ecological learning center. RIVERE proposes a “world-class ecological center” on the 4-acre site, integrating the historic structure and surrounding land into an educational campus for watershed science. This plan, if realized, would essentially conserve the swamp as a living laboratory. It aligns with the Creative Maker District’s flexible zoning by combining adaptive reuse, green infrastructure demonstration, and public access. The city has shown support in concept, and such a project could leverage the site’s environmental value rather than viewing the swamp as a hindrance.

Until any project commences, the swamp and power station lot remain private property (posted against trespassing) but functionally open space. Notably, the Friends of the Rappahannock (FOR), a local river conservation nonprofit, is very active in Fredericksburg and would likely advocate for preserving the wetland. FOR’s own education programs often take students to explore river ecology; having an intact swamp adjacent to downtown is a boon for environmental education.

In summary, while the swamp itself is not explicitly a park or preserve, it is indirectly protected by regulatory constraints (RPA buffer, floodplain rules, wetland permits).

Any development on that parcel will have to accommodate the wetland – either by preserving it or by undergoing costly mitigation. The trend appears to favor preservation: the vision of an ecological center suggests the swamp would be conserved as a habitat and teaching tool, and even a private residential development would likely leave the wetland mostly untouched (possibly as a natural amenity or because building there is impractical).

Given Fredericksburg’s broader efforts to protect the Rappahannock (e.g. the 2019 designation of the river as part of a state Scenic River and ongoing easements upstream), the site’s conservation status is cautiously positive. It is a small but important puzzle piece in the city’s green infrastructure network, recognized in planning documents as part of the “green corridor” along the river.

The provided remote-sensing and ground images offer valuable clues to past land use and current conditions in the swamp adjacent to the power plant. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) imagery of the area, which uses laser pulses to map ground elevation, reveals subtle features hidden by vegetation:

Canal and Hydropower Structures: The LiDAR digital elevation model shows a linear feature running through the swamp – likely the trace of the old mill race/power canal. It appears as a long, shallow embanked channel parallel to the river. In overhead LiDAR views, this is seen as a straight or gently curving depression with raised banks, confirming historical maps that the Fredericksburg Power Canal ran here. Toward the power plant building, LiDAR indicates some rectilinear elevated mounds and pits. These correspond to foundation remains: the power station itself (a square building footprint still extant) and possibly the bases of the surge tank silos that were part of the hydro plant. According to records, water was stored in silos (“standpipes”) before dropping onto turbines– LiDAR might be picking up the cylindrical foundation pads of those standpipes if they were on site. One image (an oblique aerial view derived from LiDAR or photogrammetry) shows a large building adjacent to a cleared, flat area and the river.

In this view, the abandoned Embrey Power Station (center-left) stands out as a light-colored rectangular structure. The tree-covered swamp extends to its right (toward the river), with the dark line of the old canal running through it. One can discern where the canal entered the power station – a straight channel leading to the building’s base. The embankment dividing the canal and river is still raised, indicating how water was once directed into the plant. This enduring topography confirms the alignment of historic infrastructure within the modern landscape.

The field photographs provide on-the-ground evidence of these interpretations:

Interior of the Fredericksburg swamp, showing standing water and numerous dead tree trunks. This image highlights altered hydrology and its impacts: the water level has risen (or stagnated) enough to drown part of the former forest, leaving a “ghost swamp” of deadwood. These snags provide perches for wildlife and will eventually fall, adding to the coarse woody debris in the marsh. New vegetation is visible in the form of wetland grasses, and shrubs clustering on slightly higher ground. The linear arrangement of some dead trees might hint at the old canal channel (trees that lined the canal banks dying when constant water was introduced). The scene is one of a recovering wetland shaped by both human infrastructure and natural processes.

From the imagery, we can infer wildlife corridors and habitat zones: The densest tree growth is along the riverbanks and higher fringes – these corridors allow animals like squirrels, raccoons, and bobcats (rare but possible) to move under cover parallel to the river. The more open marsh center, while not easy for terrestrial animals to traverse, provides rich foraging for aquatic and avian species. It likely connects to the river at certain points (e.g., small side channels during floods), so fish and amphibians can move in and out. One could imagine, during a flood, that this swamp becomes part of the river’s active channel, allowing fish to spread out and forage among the trees (an ecological benefit of floodplain connectivity). When waters recede, some fish may be trapped as the swamp becomes isolated ponds – a feast for herons and raccoons. Thus the patterns in the imagery underline the swamp’s role as a temporary extension of the river in high water and a separate wetland habitat at low water.

Human impact patterns are also visible. The straight edges of the power station and the road contrast with the organic shapes of the swamp. The fact that vegetation grows right up to the building’s foundation and even overtakes ruins (no maintained lawn here) shows that the site has been essentially left to nature for decades. However, one can see trash or man-made debris in some photos (for instance, remnants of concrete or metal possibly in the underbrush), indicating the need for clean-up. Additionally, the images hint at erosion in spots – perhaps along the banks of the canal or river where high flows have eaten away soil (look for undercut banks or sediment plumes). Addressing such erosion might be important if the area is to be made accessible or stabilized.

In conclusion, analysis of the provided images aligns well with historical records and field observations. The swamp’s current landscape is a palimpsest: the straight lines of the 19th-century canal and 20th-century power plant infrastructure are still imprinted on the terrain, even as 21st-century ecological processes blur those lines with silt, water, and vegetation. Past land uses – a transportation canal turned power canal, a hydro plant that ceased operation – left physical footprints: berms, channels, concrete ruins. Altered hydrology from the dam era transitioned to a new equilibrium after dam removal, visible in the dying trees and emerging marshland. Ecological disturbances like invasive plant takeover can be spotted in the homogeneous green mats in photos, suggesting where management may be needed. Meanwhile, the distribution of plant communities from water’s edge to upland, and the presence of structural elements like snags and thickets, maps out a variety of habitat zones: open water/marsh in the canal line (good for amphibians, insects, wading birds), dense shrub-swamp at edges (cover for songbirds, deer bedding), and drier woodland on outskirts (corridor for mammals, upland birds). The imagery reinforces that this swamp, though formed in part by human engineering, is now a vibrant semi-natural system.

Velvet shed; antlers harden; range begins to expand.

Pre‑rut sign appears (rubs & scrapes) and more daylight movement near pinch points.

Lactation likely; frequent corridor use to and from foraging cover.

Spots fade; increasing independence; first acorn feeding expected.

The intelligence gathered on the swamp adjacent to the abandoned Embrey Power Station highlights its significance and informs several recommendations:

This report has compiled available intelligence, but some gaps remain that warrant further research:

In conclusion, the swamp adjacent to Fredericksburg’s abandoned hydroelectric plant is far more than a patch of wet ground. It is a palimpsest of history – where Native American paths crossed colonial canals and where an early hydroelectric scheme played out – and now a thriving wetland ecosystem balancing on the edge of downtown. Any future decisions should treat this area as an asset to be protected and integrated thoughtfully. With informed stewardship that blends historical preservation with ecological conservation, the site can continue to provide natural benefits (habitat, flood protection, water quality) and educational value for generations. The intelligence gathered here strongly supports a vision of minimal disturbance and maximal conservation, turning what was once an industrial landscape into an urban green sanctuary that honors both its cultural and natural legacy.